In this dispute, the arbitrator concluded that there was not enough evidence to support the Claimant’s agreement to change the terms of the sale to Consignment. However, the arbitrator noted that since the Claimant did not raise any objections to the findings of the private inspection, this report would be used to evaluate whether the product met the Good Arrival Guidelines upon arrival and to establish a fair return.

The Fruit and Vegetable Dispute Resolution Corporation (DRC) has developed a series of articles summarizing past arbitration decisions. These articles will help members understand how the DRC Dispute Rules and Standards (R&S) apply in a dispute.

The DRC Dispute R&S states that all DRC arbitrations are private and confidential. As such, the names of all parties, including arbitrators and companies, are not included. A reminder that the DRC’s sole role is as administrator of the arbitration process; the DRC does not participate in any hearings. Therefore, this summary is based solely on the arbitrator’s written decision and may not reflect important information shared with the arbitrator through written briefs or verbal testimony.

ABSTRACT | SUMMARY OF FACTS | ARBITRATOR ANALYSIS AND REASONING | DRC COMMENTS

ABSTRACT

The arbitration decision relates to a dispute between parties from the United States and Canada over the claimed agreement to change the terms of the sale and the credibility of the private inspection.

Based on the findings, the arbitrator determined that there was insufficient written evidence to support the Claimant’s agreement to change the terms of the contract to Consignment. The Claimant’s non-objection upon receipt of the private inspection report was considered in determining whether the product received was within DRC Good Arrival and if not, what would be the fair return.

This summary provides an essential overview of the arbitration decision and its implications for international commercial disputes.

CASE: DRC File #19030 – Parties Domiciled – United States and Canada

SUMMARY OF FACTS:

On or about January 23, 2013, the Claimant sold a load of 1,035 cases of 5-count Canary Melons and 336 cases of 6-count Canary Melons to the Respondent, Free on Board (F.O.B.) shipping point, through a broker for USD $5.25 per case. The total invoice amount was USD $7,197.75, plus an additional $23.50 for the temperature recorder.

The load was shipped from Pompano Beach, Florida, on January 24, 2013, and it was delivered to Montreal, Quebec, on January 26, 2013.

On January 28, 2013, a private inspection was requested and performed. The inspection report revealed that the 1,035 cases of 5-count melons showed 22% surface discoloration and 4.5% bruising, while the 336 cases of 6-count melons were affected by 18% surface discoloration and 5% bruising. The pulp temperatures recorded during the inspection ranged from 49.5°F to 50.3°F.

The inspection report was shared by the Respondent to the Claimant’s broker and the broker forwarded them to the Claimant by email the same day. Communication between the Claimant, the Claimant’s broker and the Respondent shows an agreement for the Respondent to handle the product for the Claimant’s account.

On February 18, 2013, the Respondent provided an Account of Sales to the Claimant, which indicated gross sales of $5,109.80 and total expenses of $5,342.13.

In its Statement of Defense, the Respondent included invoices corresponding to the sales listed in the Account of Sales, showing sale dates between January 29 and February 13, 2013.

In the Statement of Claim, the Claimant seeks payment of $7,221.25 for the sale of the melons to the Respondent, reimbursement of $208.83 (which was deducted by the Respondent from a check issued as payment for an unrelated matter), and $600.00 in DRC filing fees. In its Statement of Defense, the Respondent has requested that the Statement of Claim be dismissed.

SUMMARY OF ARBITRATOR’S ANALYSIS AND REASONING:

I. What is the value, if anything, of the results of DRC File #19002, to the determination of this case?

The results of DRC File #19002 are not applicable to the current case due to a key difference. Although both DRC #19002 and #19030 involve inspections by IPIC International, the Claimant, in this case, agreed, by inaction, to use this private inspection service. In DRC File #19002, there was no evidence of such agreement.

II. Did the Parties Agree to Modify the Term of Sale from ‘F.O.B. Shipping Point’ to Either ‘Consignment’ or ‘Open’?

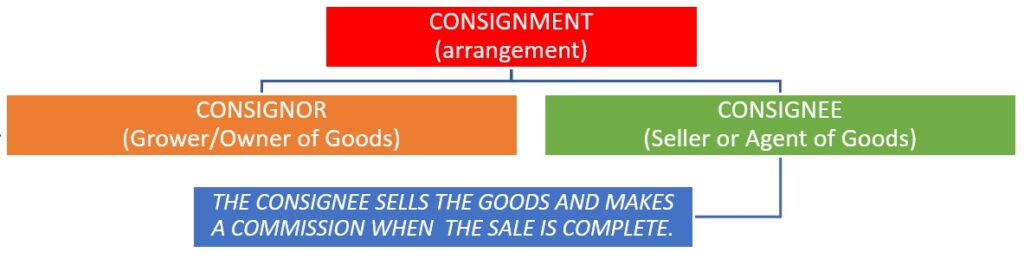

The Respondent must prove any modification of the sale terms from ‘F.O.B. Shipping Point’ to ‘Consignment’ or ‘Open Price.’ To show a change to a consignment transaction, the evidence must indicate the seller relinquished its claim for payment while allowing the handling of the load. Vague phrases like “handle the load” are not enough to establish a consignment agreement. Here, emails between the Claimant and their broker specify that the Respondent was to handle the melons “for the Claimant’s account.” The Claimant’s reply indicated he agreed but did not prove he intended to give up the right to the sales price. Thus, the Claimant has given clear authority to Respondent to sell the melons on their behalf, establishing that the sale shifted from FOB to ‘Open,’ but not to ‘Consignment.’

III. What credibility, if any, should be accorded to Inspection Report No. U114B090C?

The Respondent claims that the Claimant violated the warranty of suitable shipping conditions and has presented inspection report No. U114B090C as evidence. Since the Claimant accepted the use of this private inspection service, they have implicitly agreed to its findings.

According to the DRC Good Inspection Guidelines, private inspections cannot be treated as prima facie evidence, and the party submitting them must prove their credibility. The DRC Inspection Policy outlines that independent inspections can be recognized if they meet certain standards. The burden of proof lies with the party providing these inspections.

Upon reviewing the inspection report and the inspector’s qualifications, the arbitrator finds the inspections meet DRC Inspection Standards. The inspector’s five years with the Canadian Food Inspection Agency and his supervisory role assure his ability to conduct inspections properly. The Inspection report indicates that the inspection aligns with the required standards, including thorough sampling and accurate reporting of melon conditions. Therefore, the arbitrator concluded that the inspection report is credible evidence of the melons’ condition upon arrival.

IV. Did the Claimant Breach the Warranty of Suitable Shipping Conditions by Shipping Melons That Failed to Make Good Arrival?

According to DRC Trading Standards, the product, in this case, melons, must be in good condition for normal shipping to prevent deterioration. The DRC Good Arrival Guidelines state that melons can have a maximum of 15% total damage, no more than 8% serious damage and no more than 3% decay. The Inspection Report shows that the melons arrived with significantly higher damage—23% for the 6CT melons and 26.5% for the 5CT melons—exceeding the guidelines. Additionally, the Respondent has provided credible evidence that the transportation conditions were normal. Thus, the arbitrator concluded that the Claimant breached the warranty of suitable shipping conditions by sending damaged melons.

V. Has Respondent Provided a Proper Account of Sales Evidencing Prompt and Proper Resale of the Melons?

As the agent handling the melons, the Respondent needed to sell them in a timely manner and provide proper accounting. The Account of Sales, dated February 18, 2013, was challenged by the Claimant for not including sales dates, proper warehousing charges, and supporting freight charges. Upon review, the Account of Sales lacked sales dates but did provide a price breakdown. The Respondent later submitted all requested documents, including invoices for sales on various dates and proof of freight charges. Therefore, the arbitrator concluded that the Respondent’s Account of Sales meets the DRC Trading Standards and shows that the Respondent sold the melons promptly.

VI. Has the Claimant Met Its Burden of Proof Regarding Damages?

The Claimant is entitled to recover a “reasonable price” based on the market value of the product at the time of delivery after deducting allowed costs and expenses related to the sale. If the parties cannot agree on a reasonable price, the results of a prompt and proper sale of the product usually provide the best evidence of its fair value at delivery. This is especially true since the Claimant did not provide relevant market quotes.

As established, the Respondent’s Account of Sales, along with their defence statement, meets the commercial standards in the DRC and confirms that the Respondent promptly and appropriately resold the melons. The Respondent’s Account of Sales shows a gross return of $5,109.80 from selling the melons, which is about 71% of the initial invoice price of $7,221.25. These gross profits align with the damage percentages confirmed by inspection reports. Therefore, the arbitrator concluded that the Claimant had not met their burden of proof regarding damages linked to the Respondent’s gross sales profits from the melons.

Regarding the expenses the Respondent deducted, the DRC allows for deductions of “appropriate and usual sales charges and expenses directly incurred in handling” the product. Here, there is no evidence that the parties made any agreement about which charges or expenses could be deducted from gross sales profits. The Account of Sales shows the Respondent deducted $274.51 for inspection fees, $23.50 for temperature monitoring fees, and $3,700.00 for transportation fees related to selling the melons. The arbitrator found that these charges relating to the handling of the melons were well-documented and appropriate. Therefore, the arbitrator concluded these expenses were correctly deducted from the gross sales revenue.

On the other hand, the Respondent also deducted $1,344.12 for storage fees. Since storage fees (essentially storage charges) would have been incurred regardless of whether the melons met condition requirements, these storage fees will be denied.

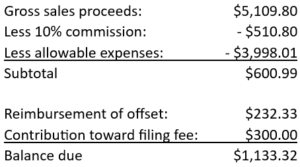

Based on the above, the arbitrator concluded that the Respondent could deduct a total of $3,998.01, leaving the Claimant with a net refundable amount of $1,111.79. Because this decision results in a net recovery for the Claimant instead of a net loss as reported initially in the Account of Sales, the arbitrator further concluded that the Respondent was not entitled to offset the initially reported loss of $232.33 with another transaction, meaning they must refund this amount to the Claimant. This will be calculated as a gross return to the Claimant of $1,344.12.

Article 48(1)(i) allows the arbitrator to issue an award for fair compensation when deemed appropriate. In this case, given that the Respondent sold the melons promptly and appropriately, they are entitled to reasonable compensation for doing so. The Respondent’s Account of Sales does not indicate that they deducted any commission from gross sales profits. Even though the Respondent did not request an order to retain a fair commission, the arbitrator concluded that such an order is appropriate for fairness in this case. A commission rate of 10% on gross sales revenue is common in the agricultural industry and is suitable here.

Article 53(1)(c) of the Mediation and Arbitration Rules of the DRC allows the arbitrator to allocate the responsibility for costs. Since the arbitrator had determined that the net sales revenue is owed to the Claimant, the arbitrator found that the Respondent is responsible for half of the Claimant’s costs, or $300.00.

ARBITRATOR’S SUMMARY DECISION:

The Respondent was ordered to pay the Claimant $1,133.32 within 30 days from the date of this Decision and Award.

DRC COMMENTS:

In this case, the arbitrator considered the results of the private inspection report to be the condition of the product upon arrival. The Claimant agreed that the Respondent would handle the product after the private inspection was shared without any objections to the findings documented in the report or the fact that it was a private inspection. For the reasons previously discussed and because the private inspection complied with the DRC Inspection Standards, the arbitrator concluded that the private inspection report would serve as credible evidence of the product’s condition upon arrival.

Another important factor in this case is the change in contract terms. It is common practice for the parties to negotiate new contract terms when the buyer receives a load in deteriorated condition. It is essential to note that when there is a disagreement between parties regarding the terms discussed, and there is no written evidence to support one party’s claims, each party bears the burden of proof for their respective arguments. The DRC encourages its members to use terms that are defined in our Trading Standards, such as “open price,” Price After Sale (PAS),” and “consignment,” to avoid interpreting vague terms such as “handling,” “protection,” or any other term not defined.

Any and all unusual agreements, such as private inspections and restrictive contract terms like “consignment,” need to be Discussed, Understood & Agreed Upon.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES:

To access the full redacted arbitration decision, click here.

Receiver Duties: Fruit and Vegetable Dispute Resolution Corporation Trading Standards s.10 (2)(b)(ii)

Good Inspection Guidelines for Fruit and Vegetable Dispute Resolution Corporation (DRC)

Solutions Newsletter Articles: